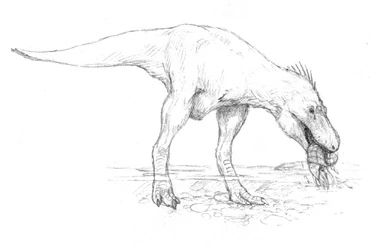

Three predators: a drak (left), a strider (middle) and a therizinosaur (right) of salmonites and their respective hunting styles.

Every year in the early spring, rivers all over the Northern Hemisphere fill with the writhing bodies of the salmonites. The spring run consists of a few gravid females, swimming downstream to lay their eggs in the sea, but the bulk of the migration is last year’s ammonitellae (larval salmonites), hauling themselves upstream. Naturally, many large animals have adapted to take advantage of this periodic smorgasbord.

During most of the year, salmonites are secure in their place near the top of the aquatic food chain. All of these cephalopods are carnivorous, and large species, like the ryömäläinen, eat everything from fish to carrion to smaller salmonites. Rapalas and other small salmonite species are often taken by herons, kingfishers, and other predatory birds, but no freshwater fish are known to eat salmonites (although lampreys often bore through the tough shell and parasitize the cephalopods). Salmonites are usually only preyed upon by the sluggish crocmanders, which hide themselves in the mud to snap up any passing cephalopod. Ironically, the rapacious mollusks actually hunt crocmanders, themselves, when the amphibians are in their vulnerable tadpole stage. All in all, the salmonites are the lords of the lake for nine months out of the year.

When the adult salmonites cease to feed and the young migrate upstream en masse, however, they attract a whole range of new predators. Terrestrial carnivores, which would normally find aquatic prey too much trouble to catch, suddenly find a new food source in their back yards, just waiting to be snapped up. Predator migration patterns, usually linked to the formosicorn herds, suddenly shift to encompass Eurasia’s rivers and their wiggling bounty.

Grisly vulgures are usually the first to are usually the first to take advantage of the migrating salmonites. These immense oviraptorosaurs are tied in intimately with the life cycle of the salmonites, relying upon the annual glut of protein to fuel the mating and egg-rearing that take place during the spring and early summer. Vulgures base their territories upon the rivers through which the salmonites migrate, and will defend their fishing rites viciously against outsiders, both predators of other species and trespassing members of their own. However, as the salmonite run progresses, the resident vulgure is usually occupied with fishing, and so other predators may partake alongside the intimidating oviraptorosaurs.

Harracks, those diminutive mattiraptors found throughout Eurasia’s forests, are quick to get past the vulgures' barriers. These little predators sometimes fish for salmonites during the rest of the year, but in the spring they collect around the streams in great numbers, stamping through the water, trying to hook the squirming mollusks with their pedal talons.

Harrack packs often catch dozens of salmonites, far more than they can eat, and bury their catch in the forest floor to eat later. Given the poor memory of the average harrack, salmonite catches often go rotten before the meat is recovered. The scent of the mollusks as they begin to rot, undetectable to most dinosaurs, quickly attracts hordes of scavenging insects and mammals such as the voracious baskerville. Such “rotting patches” are common sights in the forests in spring. The harracks, never picky eaters, are as happy to consume the rotting patches as the fresh salmonite.

Larger creatures follow in the wake of the harracks. Draks are usually the next predators to find the salmonite runs, and most drak species hunt the cephalopods in a similar way. Standing stock-still at the bank of a stream, a drak will wait for the telltale curled shell moving ponderously through the water. As the salmonite drags itself into range, the drak will spring, slamming its foot down onto the hapless mollusk. The hyper-extendable inner toe snaps down, and crack, the salmonite lies dying in the waves and the predator may feast at its leisure.

One drak species is famous for its deviance from the traditional mode of fishing, however. The polar drak, largest of Eurasia’s deinonychosaur species, comes upon the salmonites as they are swimming back up from the polar sea. Often, the ice flows have not even melted before the first elvers begin hauling themselves up the shore. These juvenile salmonites are rather small, and so the polar drak must eat a number of the little mollusks to gain much nourishment. The draks often will swim out into the water, methodically snapping up any elvers that stray into their path. This activity may be as dangerous for the polar drak as it is for the salmonites, as the selkies that feed upon the elver swarm are not above swamping the larger dinosaurs.

Later in the season, when the adults return to the sea to lay their eggs, tundraks find that a more terrestrial method of fishing is useful against larger prey. The massive predators will lean out over a stream and sweep their hands through the water in great arcs. The salmonites, flipped from the stream, meet death in the snapping jaws of the polar drak.

As the season progresses, larger predators find the salmonites more and more attractive. Errosaurs such as the strider principally hunt the steppes and stay away from the drak-ridden forests, but salmonites offer a treat that is too good to pass up. Lacking functional arms, the errosaur must wade into the water like a gargantuan stork, its head lowered and hooded eyes scanning the rushing water. When the rounded shell of a salmonite presents itself, the predator will lunge, its enormous, slicing teeth easily through the mollusks rubbery flesh. Whole groups of normally antisocial striders will collect by salmonite runs, forming fishing parties that cooperatively hunt the shelled cephalopods. It is not an accident that most errosaur species mate in the spring, when the food supply is plentiful and an errosaur’s principal enemy, the other errosaurs, are feeling social.

A strider plucking a salmonite from its aquious abode.

Striders and their kin are certainly not the only tyrannosaurs known to eat salmonites, however. Bruisers, those enigmatic little errosaurs with their deep muzzles and bone-crunching teeth, are very fond of salmonite flesh, and go far out of their way to delectable cephalopods. With their superior noses, bruisers are the first dinosaurs to find the find the rotting patches left by harracks, and often eat the entire conglomerate, rotting flesh, insects, and all. Even the massive sabre-tyrants, some of them forty feet long, have been known to scoop the little mollusks into their maws by the dozens, though these giant carnivores generally find the other animals gathered around the salmonite run to be a more rewarding meal.

Perhaps the strangest habitual predator of the salmonites during their run are the therizinosaurs. These ungainly maniraptors have been herbivores for 100 million years, but the presence of so much fresh meat seems to be irresistible even to these staunch vegetarians. Mooras often peck apart salmonite shells (presumably to get at the calcium carbonate) and even giant dorsas have been seen to snap up the mollusks, crunching the shell in their hard beaks. However, it is the yando that is the most accomplished therizinosaur fisherman.

Yando, found only in the mountains of eastern Eurasia, usually subsist only on bamboo and occasionally carrion. In spring, however, as the streams begin to fill with salmonite elvers, yando become increasingly carnivorous. Wading knee-deep into the chill water of a mountain creek, the therizinosaur will rear up, its huge manual talons slashing downward to flip the mollusks up and into the waiting maw. This method of fishing is rather like that of the polar drak, and also the Arel grizzly bear (a giant mammal). This convergence of behavior is unsurprising, as all three predators share long, powerful arms and claws. Flexible mammalian joints make the job slightly easier, but the dinosaurs seem to have no trouble dispatching the salmonites with their restrictive shoulder girdles.

Salmonites are intelligent cephalopods, and so have developed a number of defensive behaviors with which to protect themselves when they are vulnerable. Larger species, like the ryömäläinen, will haul themselves out of the water altogether and “land-lub”, pulling themselves along with powerful tentacles. A healthy ryömäläinen can survive for days out of the water, but the advantages of such locomotion are dubious at best. Giant hundraks, especially, are known for their fondness of salmonite flesh and can track a land-lubbing salmonite for miles, and seem even to enjoy the exercise. When threatened by a pursuing band of draks, a land-lubbing salmonite’s only recourse is to either re-enter the water or, if no streams are near, to climb a tree.

A frustrated drak glares up at a treed ryömäläinen.

Treed salmonites are well-documented, and, surprising though it may be, the cephalopods make good climbers. A large salmonite can grasp a nearby trunk with its suckers, and then ascend, tentacle-by-tentacle above the distance a pursuing drak can jump. Some specbiologists swear they have seen salmonties crawling from tree to tree like bizarre, tentacular squirrels, but this behavior has never been proven. Most often, a salmonite will remain in the tree until dehydration drives it back to the ground to find running water. Often, the elements will kill such an adventurer, leaving a dried husk hanging from a tree branch or stranded on the forest floor, waiting for the scavengers.

Smaller species, of course, cannot venture so far onto land. Active swimmers, such as the rapalas, propel themselves with blasts of water from their siphons, and so have no means of terrestrial locomotion. They do, however, have the ability to “bullet” or hurl themselves out of the water with great blasts from their siphons. Bulleting rapalas have been clocked at speeds of over 100 kph and accelerations that would knock a mammal unconscious. These little cephalopods can put their skill to use escaping predators, but do not launch themselves at predators as has been sometimes suggested. The force necessary to kill or stun a drak (assuming the rapala could successfully aim at and hit the head) would smash the shell of the mollusk as well. So, although not deadly, bulleting often allows smaller salmonites to evade danger by blasting away from it. Rapalas are quite good at judging distance and trajectory, and rarely land out of the water.

One defensive technique employed by the salmonites, long rumored but only recently verified, is the behavior known as “mobbing” or, more colloquially, “doing the piranha thing”. As salmonite density in a river increases, a rampaging drak or errosaur may find itself up to its knees in writhing tentacles. If the predator does not quickly vacate, it may find itself at the mercy of a hundred shelled cephalopods, each armed with grappling tentacles and a sharp, chitinous beak. Salmonites are, after all, themselves, and they are certainly smart enough to realize the strength of their numbers. Salmonites seldom mob large animals, but when the prey turn upon the predators, the scene is grizzly and the mollusks are well-fed.