Crawling over rocks and flitting through tidal pools are many and varied crustaceans. Most are familiar species, but Skull Island has its oddballs too.

Example species[]

- Osteodomus (4-8 inches long), an odd and chunky hermit crab. Large for a hermit crab, the biggest individuals have difficulty locating gastropod shells of sufficient size to fit. Innovative little opportunists, they make use of anything that even vaguely fits the bill, including hollowed bones, hence its genus. It is not uncommon to see a Skull Island fur seal skull scuttling over the rocks with spiky legs protruding.

- Lividuscutus (9-12 inches long), a dark blue-colored herbivorous lobster with delicate chelae but long, powerful legs for clinging to the wave-pounded rocks. The genus can exert remarkable grip for its size, hauling itself along the dangerous splash zone where it harvests algae from the rocks.

- Scutucaris (6-10 inches long), a flattened decapod from the slipper lobster family Scyllaridae. Scutucaris is extreme even among these squashed-looking crustaceans, with its almost two-dimensional body designed to allow it to slip into cracks and splits in the rocks of the shoreline. Predatory fish and octopi can be evaded by hiding in the narrow fissures that are common along the shattering coastline. Scutucaris also hunts in the cracks, hauling out small prey that have evaded most crabs, lobsters and other crustaceans of similar size. This crustacean is omnivorous, taking anything it comes across. The sharp-bladed chelae can pry open bivalves and snip the muscle that holds the two halves shut to get at the fleshy body inside.

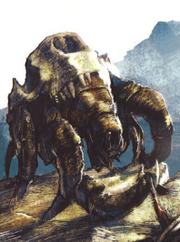

- Cunaepraedator (3-6 inches long), A stocky little land crab unlike any other, burly Cunaepraedator is a remarkable creature. Having forsaken the water, it ranges the coastal cliffs and the boarders of the jungle. Cunaepraedator has developed adaptations to live entirely free of the sea, not having to return to the water to breed. Carrying fertilized eggs in a special cavity beneath the body, females keep their precious charges moist and safe as they develop, hatching into tiny versions of their adult form. The larval stage is skipped entirely. The young crabs cling to their mother for the first days or weeks of life, crawling over her carapace and down her legs to feed, but never leaving the safety of her body. The mother crab will seek out one of the many seabird colonies that dot the island’s cliff-bordered shoreline and deposit her young there, removing them from her body by brushing against litter or delicately brushing them with her chelae. In the nest the young will grow quickly, consuming detritus and leftovers of seabirds’ meals or the remains of dead nestlings. Once the birds fledge and the nest is abandoned, the half-grown young crabs move off to join their parents in the jungle fringe as free-roaming scavengers. Cunaepraedator is also remarkable for having a second large pair of chelae. Among females, this second pair is just another set of tools for foraging, but their main function becomes apparent during the mating season, when males use their primary chelae to engage and pin those of their mates. Lifting her, chelae locked, to tilt her vulnerable underside up, the second chelae are used by the male to gently deposit seed into her egg mass. Having done so, he will let go and beat a hasty retreat out of range of her retaliatory snaps.