(→INTRODUCTION & BIOLOGY: Removed non-canon elements.) Tags: Visual edit apiedit |

(Adding categories) |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

[[Category:Central America]] |

[[Category:Central America]] |

||

[[Category:Theropods]] |

[[Category:Theropods]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Dromaeosaurs]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Maniraptorans]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Coelurosaurs]] |

||

Revision as of 15:42, 11 August 2019

INTRODUCTION & BIOLOGY

Unlike other deinonychosaurs, hesperonychids (who, despite their name, are unrelated to the cretaceous microraptorine Hesperonychus, a possible renaming of the entire family of deinonychosaurs will take place some time in the future) possess a highly flexible joint on their inner toes, rendering these talons not only hyper-extendable, but also opposable, with the other two toes of the foot (to one degree or another). While some have suggested this trait links the hesperonychids to the arbronychids, other morphological and genetic evidence suggests otherwise, and instead classifies the hesperonychids as basal deinonychosaurs related to the mattiraptors. Perhaps this peculiar pedal anatomy was originally intend for use in the trees, but today only a single hesperonychid genus (Janaata) has many arboreal proclivities. In many larger species, this unique toe joint is almost completely atrophied, changing the sickle claw back from a grasping tool to a piton.

The deinonychosaurs of South America include the apex terrestrial predators on the continent (a land of huge, tyrannosaur-like raptors and tiny to medium raptor-like tyrannosaurs), driving all of the abelisaurs native in the area into the point of extinction during the Pliocene. Although sickle-clawed coelurosaurs have a long history on the continent, the current assemblage of raptorial predators, with the exception of the enigmatic Mergaraptor, are fairly recent additions to the Neotropical fauna derived from North American hesperonychid stock. When these forms first arrived here in the Pliocene, they quickly consolidated their position with some forms attaining enormous sizes. (Ironically, the hesperonychids have since been displaced throughout much of their northern range by the invading Eurasian boreonychid draks.)

SOUTH AMERICAN SPECIES

Jagular (Jagularus robustus)

Only a few species of large animals can live in the shadow of a tropical rain-forest. Trees are too large, and grow too thickly to allow space for large forms to pass. Some ground-dwellers, however, do manage to eke out a living, and these creatures are eaten by the jagular (Jagularus robustus).

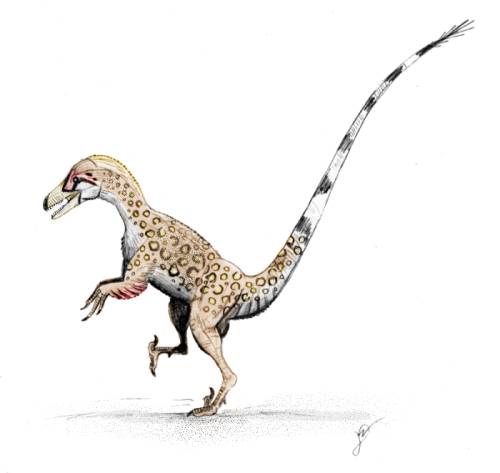

Jagulars are part of the diverse, South America radiation of hesperonychids , the descendants of North American deinonychosaurs, which migrated to South America when the two continents linked up. The bodies of these two-meter long predators are laterally compressed and their legs are rather short, allowing the animal to slip between tree trunks. Compared to other deinonychosaurs, jagulars have poor eyesight, and rely on smell and sound to hunt.

Ocelotar (Jagularus ferox)

The Ocelotar (Jagularus ferox), also known as the dwarf Jagular, is smaller than its close cousin, the jagular. These secretive theropods are completely nocturnal and have convergently evolved the a spotted pelt, like RL big-cats. Ocelotars group together in packs of about ten. In the densely wooded jungles, one can only see a few meters through the twisting vines and tree trunks and most rainforest citizens invest most of their senses in hearing or smell. The ocelotar is no exception.

Lophoraptor (Lophoraptor alecto)

Lophoraptor alecto (4.5 meters long) is a fairly large and adaptable hesperonychid that can be found from southern Mexico to Patagonia (although it avoids thickly forested areas). Lophoraptors live in large packs of up to 20 individuals with an organized method of hunting that allow them to bring down large prey. They will attack anything from young pseudosauropods down to mammals. Lophoraptors are communal breeders with the entire pack tending to the nests and young (though infant mortality is high).

Magnoraptor (Magnoraptor altas)

Growing up to lengths of 8 meters in length, the Magnoraptor, Magnoraptor atlas, which has no relation to the Cretaceous Megaraptor, is the largest dromaeosaur known to the world of Spec and one of the top predators of South America, growing larger than some other species of prehistoric dromaeosaur like Utahraptor, Achillobator, and the recently discovered Dakotaraptor who roamed North America and Asia in the past.

This giant is found throughout the continent in a variety of habitats. Magnoraptors live alone or in small family groups, patrolling a large territory and often following large herbivores on their migratory routes. They prey mostly on slow moving herbivores but will also scavenge from carcasses.

Deinonychosaurs, those versatile, predatory near-birds, have enjoyed enormous successes throughout the latter part of the Mesozoic and the Tertiary. However, diversification of form within this clade has been stunted by the demands of a deinonychosaur's life. Even tiny changes to their anatomy would result in a creature that would not be able to feed itself, and so the deinonychosaur form has stagnated, not changing appreciably in more than 100 million years.

Djanada (Janaata russelae)

There are exceptions to the rule, of course, aberrant forms that differ greatly from their progenitors and still function as organisms. One of these creatures is the djanada (Janaata russelae). Djanada live only in the cloud forests of northern South America, where moisture trapped by the rising Andes rains onto a canopy that stretches across the horizon. As lush as the Amazon, but somewhat cooler, the cloud forests are biological islands, isolated from the rest of the continent by the mountains.

The djanada is a small animal, never longer than two meters, and very lightly built, with long neck and tail and large, nimble hands. Most noteworthy, though, are a djanada's feet. The famous hyper-extendable inner toes of the deinonychosaurs have been twisted almost completely around, and now oppose the other two toes to create a powerful grasping organ. A djanada's pedal grip comes in useful for climbing trees, but is also a useful hunting tool. The predators may stand balanced on a single foot on the shadowed forest floor, or in a small stream, and wait for a small animal to happen past. When a djanada sees such a victim, it slams its foot down, pinning the hapless creature to the ground.

Because of their opposable toes, some scholars have allied djanada to the arbronychosaurs, however the creatures' internal anatomy (most notably their lack of visible hallux claws) negates this assumption. Instead, djanada are placed in their own family, Janaatidae, a sister group to Hesperonychidae, from which the djanada are undoubtedly derived.

EURASIAN AND NORTH AMERICAN SPECIES

As mentioned earlier, the hesperonychidae dromaeosaurs are not all to common in North America, being driven down to South America or to the point of oblivion thanks to the Boreonychidae draks. However, very few species of hesperonychidae thrive in North America and Eurasia today, those being the two known species of Grapple-Claw (Corriperonychus sp.) and multitude several subspecies.

Striated Grapple-Claw (Corriperonychus prima)

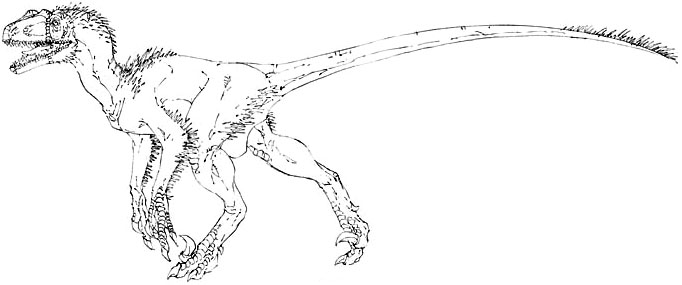

Corriperonychus prima, the striated grapple-claw, is a less a species than a complex of closely-related deinonychosaurs that live from the forests of the Northeast to the deserts of the Southwest. The exact number of subspecies is a point of debate, but five races are generally accepted by the scientific community: (clockwise from top) C. p. montanus, C. p. appalachiensis, C. p. floridensis, C. p. horridus, and C. p. mexicanus (considerable by some to be a distinct species, since it rarely comes in contact with any other race).

Striated grapple-claw subspecies are arranged in a loose arc, each subspecies able to hybridize with those adjacent to it, but genetically incompatible with those farther away. Thus, the C. p. montanus may cross-breed with C. p. appalachiensis, but not with C. p. mexicanus.

Such lack of genetic distinction is shared by the other Corriperonychus species, C. lupinoides is thought to be the product of the species' rapid radiation from a common ancestor in the very recent past, perhaps as little as 2 million years ago.

Like the other grapple-claw species, striated grapple-claws are stealthy hunters that stalk their prey over some time and then leap upon the hapless herbivore and throttle it with their powerful talons.

Plains Grapple-Claw (Corriperonychus lupinoides)

The plains grapple-claw, Corriperonychus lupinoides is the principal small predator of the great plains of the North American interior. These creatures are stealthy stalkers that can bring down a large herbivore with a swipe of their powerful feet and the slash of a sharp-clawed hand. Plains grapple-claws range from 1.5 meters in length (C. l. incultus) to the almost 4 meter long C. l. maximus.

Like its close relative, the Striated grapple-claw (C. prima), Corriperonychus lupinoides exists in a number of distinct subspecies (clockwise from top: C. l. venator, C. l. maximus, C. l. incultus, and C. l. mongoliensis). All of these subspecies are capable of inter breeding only with those directly adjacent. Thus, while the northernmost-dwelling C. l. venator may breed with C. l. maximus, and C. l. mongolonensis, it may not do so with C. l. incultus.

~Brian Choo, Daniel Bensen , and David Namen